2025 Colorado Getaways: Vail Valley

Vail Valley is home to an endless array of summer outdoor pursuits

By Jon Rizzi

“WE OWE IT TO THE FOUNDERS AND THE FUTURES.”

So says Cherry Hills Country Club President David Keyte of the substantial investment that he and current members are making in one of Colorado’s most storied private clubs as it enters its 100th year. “It’s our legacy to improve it when we can.”

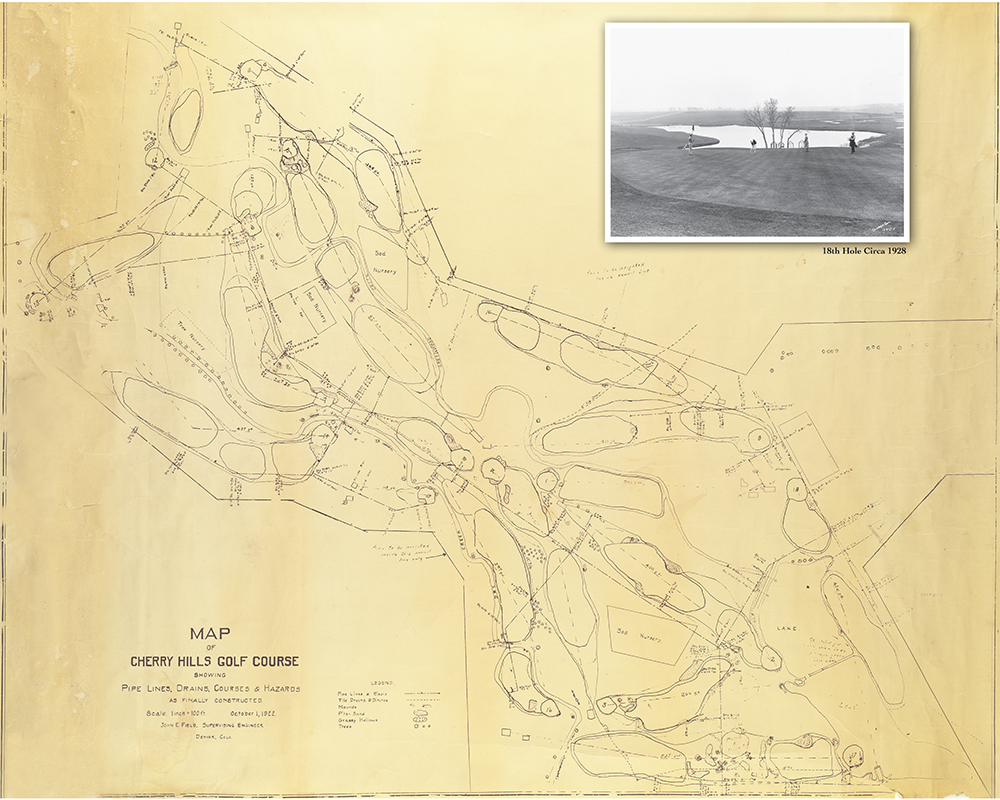

Those improvements include a $67 million clubhouse expansion that will bring the total square footage—including a remodeled basement and a new second story—to 96,000. They also include two golf-course initiatives: the purchase of properties adjacent to the famous finishing hole to satisfy the ever-increasing space requirements of championship golf; and the completion of a restoration of the golf course’s original 1922 William S. Flynn layout by Denver-based Eric Iverson of Tom Doak’s Renaissance Golf team.

THE CLUBHOUSE

Although the centenary is 2022, “the goal is to have all the pieces in place by 2023, when we host the 2023 U.S. Amateur—our 14th major championship,” Keyte says. However, he also points out that the largest and most conspicuous of those pieces will be ready before 2022 is over. “We’re building the clubhouse in honor of our 100th anniversary, so we’re targeting a temporary certificate of occupancy by November 1.”

(During construction, the club has conducted meetings and social events at the former restaurant at Union and Ulster in the Denver Tech Center and golf operations from modular units adjacent to the course.)

For its size, cost and high visibility, the clubhouse project has received the most attention. Designed by Connecticut-based Mark P. Finlay Architects and built by Colorado’s JHL Constructors, the addition retains much of the Tudor structure’s architectural style while completely overhauling its south side, starting with replacing its 100-year-old foundation.

The formerly low-ceilinged basement will now house a sizable fitness center right off the pool area, a golf bar with simulators, yoga and Pilates studios and offices for club administration. On the ground floor, banquet space will coexist with a variety of member areas, including NanaWalled indoor-outdoor sections. Only the far north side—which underwent a renovation prior to the 2005 U.S. Women’s Open and houses the golf shop, men’s locker room and Hall of Champions—will remain largely unchanged.

Most dramatically, the second-story addition will feature meeting rooms and a member’s dining room with majestic west-facing views from above the tree-lined course towards the Rockies. “You’d be amazed what a difference 25 feet in elevation makes,” says General Manager/COO Lance Sabella, who joined the club from Lakeside Country Club in Burbank last year.

Preliminarily called Arnie’s, in honor of the winner of the 1960 U.S. Open at Cherry Hills, the steakhouse-style restaurant will also boast items from the club’s cherished collection of Arnold Palmer memorabilia. Some of it will also presumably remain in the display in the Hall of Champions, which spotlights every national championship hosted by the club—from the 1938 U.S. Open (the first one ever contested west of the Mississippi River and the last in which the winner [Ralph Guldahl] wore a tie) through the 2014 BMW Championship.

THE COURSE

“We have to host a major tournament every 10 years; it’s in our bylaws,” Keyte explains. “Cherry Hills started exclusively as a golf club, but when it fell on hard times during the Great Depression, it became a country club. We continue as a country club, but the membership understands the golf course is the number-one priority.”

Designed by Philadelphian William S. Flynn—the man who finished Pine Valley after George Crump’s death, and whose credits include Shinnecock Hills and The Country Club in Brookline—Cherry Hills featured many elements of those legendary layouts and some novel ones, such as the figure-eight routing of the front nine and the country’s first par-5 island green on hole 17.

Like most courses from the “Golden Age of Golf Course Architecture,” Cherry Hills defends itself not with length—at altitude, its 7,375 yards had as little bearing on players in the 2014 BMW as its 6,888 yards had in the 1938 U.S. Open—but with angles, shot placement, deception, temptation, strategic hazards and the subtle tilt and contour of the putting surfaces.

“The first time playing it, everybody thinks they’re going to eat it up,” Keyte says. “Then they leave hungry.”

However, he and the board also know that to continue hosting major championships, the club needs room for hospitality tents, access for parking and shuttles. So, the club purchased two properties—one east of the 18th fairway that currently has a home on it; the other, a five-acre lot at the corner of University and Quincy.

“We wanted to make a statement that we could host,” Keyte says of the acquisitions. Could the additional land behind the 18th tee also create a new back teeing area for a 484-yard hole that members play as a par 5 but the pros play as a 4?

“I’m not sure that hole will get better if it’s longer,” Eric Iverson of Renaissance Golf says. “Flynn’s original tee was the peninsula (currently 454 yards). As the tee space grew to the back corner, you had to aim further east, taking the water out of the equation off the tee. If we can maintain the angle of the tee shot that Flynn originally intended, that would work, but we don’t want to do anything rash.”

How to balance the hallmark strategies of great architecture to keep challenging the game’s elite? Iverson has dealt with questions like this since 2008, when Renaissance performed the first of three phases in its restoration of the original Flynn design.

A RENAISSANCE BEGINS

Renaissance’s involvement began a “reset” of a course that Golf Digest currently ranks 73rd on its list of 100 Greatest Courses, slightly higher than where of Golf and Golfweek place it. Retaining and improving its place among the Top 100 factored into the “reset.”

During the first phase, which coincided with the replacement of the course’s irrigation system and halfway house, Renaissance agreed to “add length when reasonable.” Which it did, finding extra length on holes eight, nine and 16, while bringing back the original strategies that time, tree growth and various “beautification” projects had altered.

The team returned the greens and fairways to their initial dimensions, and the removal, relocation and reintroduction of tees, trees and bunkers on holes throughout the course tellingly revealed the architect’s original vision. Most noticeably, the 17th green, which had sprouted a mini-arboretum behind it, regained its intimidating, treeless island identity.

Renaissance’s restoration continued in 2016, as the team edged and shaped every bunker. By removing some larger trees at the elbow of the left-dogleg par-4 seventh, they rekindled the temptation to drive the green despite the risk of rolling into Little Dry Creek or the center fairway bunker 100 yards out. On the following hole, a long 222-yard par 3, Doak and Iverson also expanded the green to flirt more with the creek to the right.

THE CREEK RESTORATION

The “culminating project” in the course renaissance, according to the club’s PGA Head Professional Andrew Shuck, who arrived last April from Charlotte Country Club, is the Little Dry Creek restoration that is going on right now.

Entering the property from the south, near the 17th tee, Little Dry Creek flows northwest through the course for about a mile before crossing in front of the 13th green as it exits the property. On Flynn’s drawings and the original engineer’s report, the creek’s journey takes it right next to the greens on holes seven, eight, 14, 15 and 16. It also runs along the right of the 16th fairway before crossing it near the green. “You can see from all the hole drawings that Flynn routed the holes and implemented strategy based on the hazard,” Iverson says.

This changed during the 1980s, when the creek was straightened, channelized, bouldered and, in some cases, moved 30 to 40 feet away from the fairway or green to mitigate flooding.

Over time, however, these changes created “pinch points” (areas that slow water and cause flooding) by the 14th and 16th greens.

When the club brought in an engineering firm to solve the new flooding problems, the opportunity arose to return the creek to its strategic importance.

To help reduce the flooding and “pinch points,” the engineers and Iverson made the 90-degree creek banks approximately 45 degrees and removed virtually every boulder—except those needed for erosion control and pipe crossings.

“On 16, there’s a five-foot ridge right of the fairway into the rough where the creek used to be,” Cherry Hills Director of Grounds Josh Hester explains. “Now the creek is 40 feet to the right. On the par-3 15th, the boulders along the creek raised the banks, and over time those banks have risen even further. The added elevation eliminated the natural slope to the water—and reduced the risk of your ball going in.”

With the full support of the club, the Army Corps of Engineers, the USGA and Hester worked with Iverson to return the natural meander to the creek and maximize the natural slope towards the water. Riffle structures, which create that “babbling brook sound,” and larger pooling areas keep the creek flowing.

The project will make the affected holes even more formidable. A shot pushed right of the green on the par-4 seventh, for example, will dribble into the creek, as will one on the par-3 eighth, where the widened green now sits much closer to the water and features added mounding on its left fringe—opposite the creek—that can kick the ball onto the green.

On the long, sweeping par-4 14th, the creek cuts in to replace the bunker fronting the left of the green and runs along the entire left flank of the putting surface. “It was already a great hole,” Iverson says, “and it’s going to be more dramatic now.”

The architect also got rid of the back two bunkers on the par-3 15th to cozy the creek up to the green. The hole—which Flynn designed to be 115 yards but played at 242 during the 1985 PGA Championship—will now feature a tee directly behind the 14th green and adjacent to the creek. From this tee, the 150-yard hole now features water along its entire left side, creating a more daunting tee shot. “That hole was meant to be played along the creek,” Iverson says, noting that for tournament play, the longer tees on the hill are still available and could be alternated on different days during championships.

A footbridge spanning the creek leads to a new tee bordering the left side of the creek on the 465-yard 16th. The water follows the curl of the fairway, which features two pooling areas where a lone bunker once caught blocked drives. The stream cuts across the fairway about 100 yards out and remains in play on the left and rear of the green.

“There’s nothing going on with that creek that makes things easier,” Keyte laughs. “We expect to have the work completed by April 1st,” Hester says. “That gives us two full growing seasons before the U.S. Amateur in August, 2023.”

By 2023, the clubhouse will already have reopened, and Cherry Hills Country Club will be poised for another century of legacy building and championship golf. For this, Keyte credits the visionary work of the club presidents and committee chairs who preceded him and the “perfect team” the club now has in place.

“We’re on such a great trajectory,” he says. “It’s a big step between a country club and a major championship golf course. We’ve achieved it many times—and we’re dead-eyed focused on achieving it again.”

Jon Rizzi is the editor of Colorado AvidGolfer.

This article can also be found in the 2022 Spring Issue of Colorado AvidGolfer.

Colorado AvidGolfer is the state’s leading resource for golf and the lifestyle that surrounds it, publishing eight issues annually and proudly delivering daily content via coloradoavidgolfer.com.

Vail Valley is home to an endless array of summer outdoor pursuits