Drive Away Hunger Golf Classic 2025

Join Community Table on August 25 at Fossil Trace Golf Club

By Dan O’Neill

IN HIS DESK in St. Louis, his office in Paradise Valley, Ariz., his closets, his drawers … Hale Irwin has searched everywhere, looking for a thin legal pad, yellow paper that changed his life 30 years ago—and changed golf history as well.

“I kept it, I hid it and I cannot find it,” Irwin said. “I’ve looked all over and I cannot find it, but if I do, I’d put it in the Hall of Fame, because I really do think it’s something that inspired me. It got me thinking what was possible again.”

In late 1989, Irwin sat down with a pen and that pad of paper. After winning The Memorial in 1985, Irwin started a golf course design business, which had become more and more engrossing. At the same time, his golf had become less and less rewarding.

More than four years had passed since that last PGA Tour win. Ten years had passed since his second U.S. Open victory at the Inverness in 1979. Over the previous five seasons, a man with 17 wins, 41 top-3s and 141 top-10s had collected just two top-3s and nine top-10s. A man declining in the late innings of a robust career, sat down with that paper and pen, and reflected.

“I was still hitting the golf shots, that wasn’t a problem,” Irwin recalled. “It was remembering how to play, how to go out and put one good shot after another together. So after five years of frustration, I kind of thought, ‘You know, I’m enjoying the design work and all of that … this is going to have to be a different year, or I’m hanging it up, because this is no fun.

“I wrote down all that stuff, all the things I could remember about the tournaments I won. And what I couldn’t remember about a particular tournament, I would set it aside and come back to it. Anyway, it got me thinking about playing again, how to go out and become the player that I hopefully was before.

“And I could feel once the season got started, there was a little more bounce to my step … I felt closer to what I was trying to accomplish as a player. So as the season went on, I could feel it coming together.”

Reinvention was nothing new for Irwin. In 1963, the standout athlete from Boulder High School came to the University of Colorado set on playing quarterback and golf. But as a sophomore in 1964, his football aspirations stalled when coach Eddie Crowder turned to Bernie McCall behind center. Irwin had a choice—change positions, or punt football to focus on golf. He chose the former.

And over the next two school years, when he wasn’t setting the school’s single-season record for stroke average (which still stands), when he wasn’t winning an NCAA individual golf championship, he became a two-time All Big Eight Conference defensive back. Years later, he was named to Colorado’s 25-man All Century Football Team.

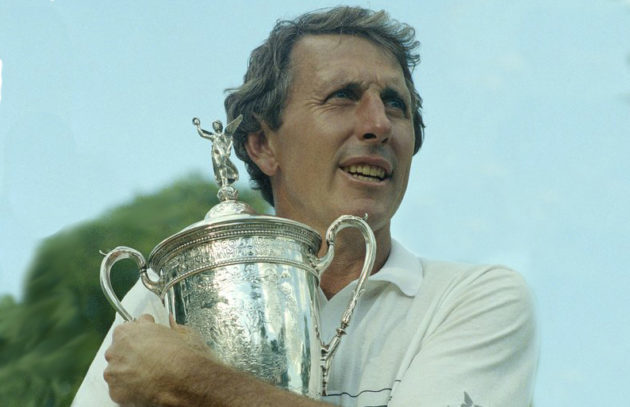

Thus, what Irwin set in motion with a pad of paper can be considered improbable, not impossible. What he achieved 30 years ago, shortly after his 45th birthday in 1990, was unprecedented, not unthinkable. With 72 holes of regulation and 19 holes of overtime, his third U.S. Open victory was not for the ages, it was for the ageless.

“Was the win at Medinah a shocker?” Irwin asked rhetorically, “No. Was it a surprise? Well, yeah, because you never think you’re going to win. You hope to win, but … In my mind, the tables were set to do something around that time period because I could feel it coming. And it just happened to be that week, when it all came together.”

Irwin already stood among golf’s tall timber. His two aforementioned wins were the “Massacre at Winged Foot” in 1974— where his winning score was 7-over par— and another at Inverness in 1979. He threatened a third at Winged Foot in 1984, taking a one-shot lead into the final round. But his father was dying from prostate cancer, a narrative that became overbearing and Irwin collapsed under a final round 79.

“Here I was 10 years removed from the ’74 win, leading going into the last round and thinking, Wouldn’t it be great to win another one, selfishly for me and even more so for my dad. I just built that thing up to something that I couldn’t sustain.”

Six years later at Medinah, Irwin was four strokes and 17 players behind after the third round. Even Sir Edmund Hillary would find that a tough climb.

That evening in Chicago, Irwin went to dinner with his wife Sally and daughter Becky. Sunday would be Father’s Day, and 18-year-old Becky presented her dad with a tie. The gift proved prophetic. “I never throw out a tie, so I still have it somewhere,” Irwin said. “I can’t remember, couldn’t tell you which one it is. But I’m sure Becky could go to my closet right now and pick it out.”

The next day, switching to a heavier putter, Irwin found something midway through the final round. He birdied four in a row, five of the last eight and covered nine holes in 31 swings. As he stood over an imposing 45-foot putt for a birdie at 18, he was 7-under, believing 8-under would have a chance. The long roll dropped in, perfectly paced, perfectly placed.

The gallery exploded. Normally stolid, Irwin channeled his football past, took it to the house and celebrated in the end zone. He circled the ropes, high-fived spectators, pumped his fists and blew a two-handed kiss. “After all these years, you would be shocked by how many people have come up and said, ‘Hey, I high-fived you in 1990,’” Irwin said, laughing. “I mean if you go back and look at how many I actually high-fived it was … oh, let’s say, seven or eight people.”

An hour behind in the last pairing, 34-year-old Mike Donald validated all the excitement and the Father’s Day tie. Leading by one, Donald bogeyed No. 16 to drop into a knot with Irwin. Moments later, on the 18th green, his 40-foot putt to win outright expired agonizingly short of the hole. The championship went to a playoff.

In today’s world, things would have been decided promptly, with a two-hole playoff format adopted in 2018. But in 1990, it was the full Monty—or the full Monday—18 holes long. When it arrived, neither of the nervous combatants was especially sharp. With three holes remaining, it appeared Donald was in command, 1-over par and two shots better.

Irwin birdied 16 with a sensational 2-iron and the difference was one. At 18, Donald still led by one when he hit driver off the tee, hooking it into the trees. When his 18-foot putt narrowly failed to save par, the playoff went to sudden death—the first in U.S. Open history.

The players returned to No. 1, a hole Donald had birdied three consecutive times. But this time, his wedge settled 25 feet short of the flag, leaving a door open. Irwin’s 103-yard approach landed 10 feet from home. Donald’s long putt went wide right, Irwin’s disappeared in the hole.

Fifteen days after his 45th birthday, one day after his high-five trot, Hale Irwin was again the U.S. Open champion.

There would be more highlights to come, and quickly. Six days later in Harrison, N.Y., an exhausted Irwin edged Paul Azinger to win the Buick Classic, becoming the first since Billy Casper to follow a U.S. Open win with a victory in the next tournament. Irwin would win one more PGA Tour event at age 48 and then dominate the Senior Tour (now PGA Tour Champions), becoming the career leader with 45 wins.

Now 75, Irwin continues his design business, where he recently collaborated with Broomfield-based iConGolf Studio on a $45 million renovation of Denver’s iconic City Park Golf Course. He also is involved in a new multi-media digital project, entitled Keeler1930. His playing career has dwindled to an occasional Champions appearance. That said, he enjoys reminiscing about his “Miracle at Medinah,” or any of his successes.

Irwin always has been among the more cerebral figures in sports. He recognizes the physicality of today’s game, as well as the financial parameters, have changed. His distinction as the oldest winner in U.S. Open history has enjoyed a long shelf life. He would not be surprised if it lasts longer still.

“I mean it’s just slam it, and chase it, and hit another wedge and make a putt,” Irwin said. “Physically, the way they swing at the ball now, with the pressure and the leverage they’re putting on joints … I don’t know if they are physically going to be there at 45.

There s talent there, but I don’t know if the interest level will be there. It’s almost like it’s a short-term thing. The kids are going to go out there and, whatever it takes for 10 years, they’re going to do it. By the time they’re 35-years-old they might not have it anymore. Add another 10 years to that, you’re 45 and I don’t know.”

The game—like seemingly everything else in our culture—has been altered even more dramatically this year. The championship Irwin captured three times has been moved from its traditional June home to a tentative Sept. 17-20 slot. It has eliminated qualifying and filled its field with exemptions.

And as the novel coronavirus pandemic persists and precautions prevail, you can bet there won’t be any emotional high fives with galleries at Winged Foot this time. There might not be any galleries at all.

“I find it very disheartening,” said Irwin, whose son, Steve, a long time Colorado amateur, qualified into the 2011 U.S. Open. “I often call it our national Open and to call it ‘Open’ now is a misnomer. How do you have a U.S. Open in New York, one of the hot spots in our game, and have no people out there?

“It’s going to be really, really odd. The USGA, I’m sure, and all of the golfers around the world are just agonizing over this … You get so much energy from the galleries and the crowds and the cheering. It just seems so misplaced.”

Speaking of misplaced, somewhere there exists a pad of yellow paper, paper that changed Hale Irwin’s life 30 years ago, and gave the U.S. Open one of its defining stories.

“I know it’s around somewhere,” Irwin said. “I’d love to see it again. One of these days, I will.”

Dan O’Neill has been a golf writer for 32 years. He writes for Morning Read and works with Fox Golf as an editorial consultant.

This article was also featured in the August/September 2020 issue of Colorado AvidGolfer.

Colorado AvidGolfer is the state’s leading resource for golf and the lifestyle that surrounds it, publishing eight issues annually and proudly delivering daily content via coloradoavidgolfer.com.

Join Community Table on August 25 at Fossil Trace Golf Club

Steamboat Springs is like a secret only you and your friends know

Vail Valley is home to an endless array of summer outdoor pursuits