Aurora’s Davis Bryant hopes to keep a good thing going

Aurora native gets pair of Top 10s in his second pro season

By Jon Rizzi

A true giant left us this weekend when broad-shouldered, 6-foot-3 Tom Weiskopf lost a two-year battle with pancreatic cancer at the age of 79. Possessed of a beautiful swing and a fiery temperament, “The Towering Inferno” won 28 professional events, including 16 victories on the PGA TOUR. He captured his lone major at the 1973 Open at Royal Troon.

Twenty years later, he lost by a shot to Jack Nicklaus in the 1993 U.S. Senior Open at Cherry Hills—writing another chapter in a rivalry between former Ohio State Buckeyes that rarely resulted in Weiskopf’s favor.

One of the times Weiskopf did best the Golden Bear came two years later, as he finished four strokes clear of Nicklaus to take the 1995 U.S. Senior Open at Congressional—his only senior major win.

In Colorado, Weiskopf won the 1982 Jerry Ford Invitational at Vail Golf Club, but he left his mark in the Centennial State during his highly successful second career that saw him design more than 80 courses in 10 different countries (including Loch Lomond in Scotland) and 18 different states (including Troon North, TPC Scottsdale, Forest Highlands and Seven Canyons in Arizona; Yellowstone Club in Montana; and Double Eagle in Ohio).

Teaming with architect Jay Morrish—who had worked with Nicklaus on both Castle Pines Golf Club and The Country Club at Castle Pines—Weiskopf designed Grandote Peaks Golf Club at the base of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in La Veta. The popular layout opened in 1988 and established Weiskopf’s reputation for mountain course design. (After closing in 2016, Grandote reopened nine holes this year, and its committed new owners foresee all 18 in play by May.)

In 1995, Weiskopf and Morrish continued to build their Colorado portfolio with the private Eagle Springs Golf Club in Wolcott. However, by the time the daily-fee Ridge at Castle Pines North debuted two years later, he and Morrish had parted ways.

The split reportedly cost them the job at Aspen Glen, for which they had completed the layout. Ownership elected to use Nicklaus.

“Jack beat me in my first career, and I want to beat him in my second,” Weiskopf told architect Phil Smith over lunch in 1999.

Like Morrish, Smith worked for Nicklaus. So Weiskopf hired him.

“Everyone was shocked that I left Jack for Tom,” Smith says. “They remembered his temper on the course, but that was always self-directed. He’d get mad at himself. As a course designer, Tom always wanted collaboration.”

Weiskopf and Smith made a great team. “We meshed so well because Jack had sponged off Jay Morrish and Bob Cupp. Tom learned the same principles from Jay, so for me to work with Tom made for an easy transition.”

A more difficult transition came as the new millennium dawned. While building Yellowstone Club in Montana, the hard-living Weiskopf quit alcohol two days after ringing in 2000. “I just looked at the mountains and said, ‘Why do I do this to myself?’” he reflected in a piece in Colorado AvidGolfer. “Everything bad that had happened in my life was caused by drinking. I’m in this beautiful place, and I said, ‘I’m not going to do this anymore.’”

“He just decided to stop,” Smith remembers. For the next 23 years, alcohol never passed Weiskopf’s lips. “He didn’t go to AA or any program. For somebody who drank as much as he drank to have the willpower and the mental capacity to stop drinking was truly inspirational.”

With Smith, Weiskopf created courses at Catamount Ranch in Steamboat Springs (2000), Flying Horse in Colorado Springs (2005) and Adams Mountain—the original name of Frost Creek Club—in Eagle in 2007.

Each of those boasts at least one drivable par 4, a Weiskopf signature inspired by the great courses of Scotland. “Those holes at St. Andrews and Troon really stuck with him,” Smith remembers.

Another principle: “Whatever we do, let’s make sure every hole from its inception looks like it fits. Each hole needs to feel like it’s supposed to be there, not forced. We want people to feel comfortable on the tee.”

Weiskopf wasn’t averse to moving more dirt to make a hole look more natural, either. “The key was to have your eye equally entertained by the golf in foreground and the surroundings in background,” Smith says.

During the years the pair collaborated, most of the three-dozen surroundings in which they worked were famously spectacular—Sedona, Big Sky, Lake Tahoe, Coeur d’Alene, Jackson Hole, Kauai—and so were the courses they put there.

On his own after the recession, Smith designed Flying Horse North, the stunning companion course to the one he and Weiskopf had done at The Club at Flying Horse. By the time it opened in Colorado’s Black Forest in 2020, the architect and designer had linked up again as Weiskopf-Smith.

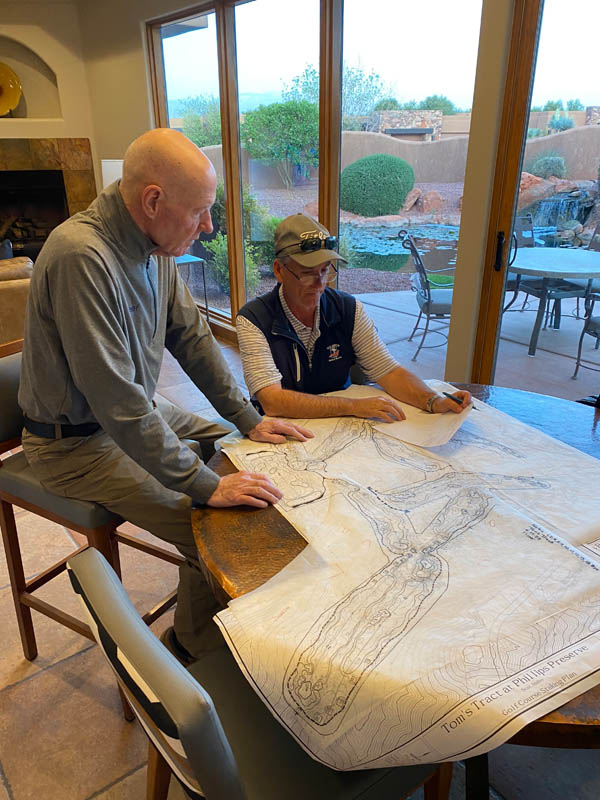

As Weiskopf waged his heroic two-year battle with pancreatic cancer, he and Smith collaborated until the very end. Their stunner at Black Desert, near St. George, will open in the spring, and construction of a course outside of Boise is well under way. By 2024 Spanish Peaks in Montana will sport a 10-hole par-3 course called “The Legacy-Tom’s Ten,” based on Weiskopf’s favorite holes from around the world.

“Tom was just the right amount of famous,” Smith says. “When I would go out with Jack Nicklaus, it was like being with Michael Jackson. But even though he filled a room when he walked into it, people didn’t always know who Tom was. He was always happy to be recognized and never short with fans. I always admired that about him.”

Weiskopf, however, never received recognition from the World Golf Hall of Fame, something that rankled him. In addition to more than two dozen professional wins, he also finished second in four Masters (a record for a non-champion), spent 10 years as a commentator for NBC and ABC/ESPN and has created an incomparable catalog of courses.

He had the misfortune of playing in the shadow of Nicklaus and often his fiercest competitors were himself and his drinking. Still, the scope and quality of Weiskopf’s work makes him as worthy—if not more worthy—of induction than some of the individuals whom the Hall has honored.

Colorado AvidGolfer Magazine is the state’s leading resource for golf and the lifestyle that surrounds it, publishing eight issues annually and proudly delivering daily content via coloradoavidgolfer.com.

Aurora native gets pair of Top 10s in his second pro season

Quail Dunes is one of the best eastern Colorado courses

The Beast of Berthound Returns at The Ascendant Presented by Blue

Callaway’s new X-Forged and X-Forged Max irons reject tech clutter in favor of old-school austerity