Drive Away Hunger Golf Classic 2025

Join Community Table on August 25 at Fossil Trace Golf Club

By Tom Ferrell

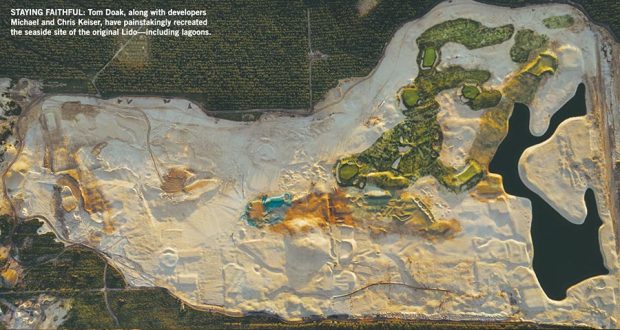

ON THE SURFACE, there are few similarities between the Atlantic shores of Long Island and the pine-studded sand deposits of central Wisconsin. Pursue the art of deeper vision, however, and you sometimes stumble upon unlikely opportunities. After all, Herb Kohler and Pete Dye engineered an homage to Irish golf at Whistling Straits, which sits on the Lake Michigan shoreline and has host- ed a slew of majors, including this year’s Ryder Cup. But while golf is full of “inspired by” and “in the spirit of” projects, the sons of one of golf’s most famous entrepreneurs are going beyond such guiding principles to re-create the holy grail of golf’s Golden Age—the Lido.

Mike Keiser, founder of Bandon Dunes in Oregon, and sons Michael and Chris, owners and operators of Sand Valley Golf Resort, are deep- ly tied to natural golf sites and designs. So it turned some heads when Michael and Chris announced plans to authentically re-stage a course renowned in its time as an engineering marvel.

“I had gotten fascinated with the story of the Lido—C.B. Macdonald’s great course built in the tidal marshes of Long Island,” Michael Keis- er says. “When it opened in 1918, it was the crown jewel of golf’s early Golden Age.”

The eminent golf writer Bernard Darwin gushed over the Lido when he visited it shortly after opening. “Besides having a genius for golf- ing architecture, Macdonald must have the imagination of a poet and a seer. Otherwise, he could never have envisaged making such a course.”

Macdonald’s long-time associate Seth Raynor moved more than 2 million cubic yards of sand to fashion a rolling, rollicking site on what had been perfectly flat wetlands. His work changed the entire idea of course construction. Macdonald then carefully laid out his famous template holes—including Alps, Cape, Channel and Redan—and unveiled a golf experience like none the world had ever seen.

“Our golf ancestors could have desired nothing better,” Darwin concluded. “The Lido is among the world’s very best.”

Macdonald, already famous for his designs at Chicago Golf Club and National Golf Links of America, pulled out all the stops at the Lido. He spent a then-astronomical $1.43 million building the course. As part of his bold promotion, he sponsored a contest for armchair architects, promising to integrate the winner’s hole design into the final layout. Naturally, the winner was an obscure English architect named Alister MacKenzie, who would go on to become one of the lions of the craft.

But when World War II broke out, the U.S. Navy bought the land and destroyed the golf course, and thus a legend was born.

“My dad (Mike Keiser) has always dreamed of recreating the Lido,” Michael Keiser says. “That was his original thought at Bandon for what became Old Mac (Old Macdonald). But there was just no way to truly recreate the site or conditions.”

At least, according to conventional wisdom. The Keiser brothers soon discovered the work of fellow Chicago resident and amateur golf historian Peter Flory. Using golf gaming technology, Flory had set about creating a virtual re-creation of the Lido, incorporating survey maps accurate to approximately one inch. His quest captured the imagination of many golf course architecture students, including the Keisers and Tom Doak, who discussed Flory’s achievement while working on the routing for Sand Valley’s third course.

“We thought it might be possible to clear a site and sculpt it using Peter’s work as a guide. And that idea kind of took off.”

Anyone who has played or studied Tom Doak’s course design and written work has reaped the benefits of his painstaking attention to detail and authenticity. As the Lido discussion careened toward action, he peppered the Keisers with questions and identified key hurdles that would have to be cleared. First, the grade of the land had to match exactly the Lido site. Given that Raynor constructed Lido only after moving some two million cubic yards of sand, and the Sand Valley region is—obviously—gifted with ample amounts of sand, this seemed possible.

Then the came the more capricious issue of wind. The original Lido occupied a windswept tidal basin devoid of trees or other vegetation. Wind was not just a daily condition; it was a design factor. So, if the re-creation were to be viable, orientation and wind would need to be similar, and no one had ever compared the winds of Nekoosa, Wisconsin, to those of Long Beach, New York.

“We felt like we had to follow the cardinal points of the original in terms of compass points—the holes needed to play in the same direction,” says Michael Keiser. “The next question then was, how does the wind line up?”

Using wind roses—overlays of NOAA re- cords denoting wind speeds and directions over 12-month periods—the Keiser brothers made a startling and welcome discovery. “The 12-month wind roses of the Wisconsin site and the Long Island site were almost identical,” Keiser says. “This was the go/no-go decision, and we all agreed: Go!”

The “go” decision ironically benefited from a “no-go” decision on the third Sand Valley Re- sort course. That project required significant financing, and with the COVID-19 pandemic sweeping across the world in early 2020, the Keisers hit the hold button. The Lido, however, offered a unique financing opportunity—a private club model with weekday access to resort guests—and the timing that felt right to both Doak and the developers. Guided by Flory’s extraordinary renderings (see them at thelido.com), the team began work in 2020. Preview play for members will begin in 2022, with the grand opening scheduled for 2023.

A project like re-creating the Lido is inevitably going to leave a lasting influence on its developers. Michael Keiser says it has already changed his thinking toward golf design and construction: “One thing Lido has taught me is to go aggressively after the very best possible holes. That was C.B. Macdonald’s idea with the original. It was big and audacious, and he embraced that.” The Keiser brothers’ future projects—a hopeful rumor has them interested in a parcel of sandy Colorado land, among other sites—will certainly reflect this new boldness.

“There’s no reason to be afraid of engineer- ing and construction,” Keiser, Jr. notes. Yes, nature does the finest work, but when you get the opportunity to dial it up to 11 and make ordinary holes extraordinary, do it!”

Turning it up to 11. That’s always been the Lido way—both then and now.

This article was also featured in the Fall 2021 Issue of Colorado AvidGolfer.

Colorado AvidGolfer is the state’s leading resource for golf and the lifestyle that surrounds it, publishing eight issues annually and proudly delivering daily content via coloradoavidgolfer.com.

Join Community Table on August 25 at Fossil Trace Golf Club

Steamboat Springs is like a secret only you and your friends know

Vail Valley is home to an endless array of summer outdoor pursuits