CSU Grad Davis Bryant Discusses His Rise as a Pro Golfer

Colorado State grad Davis Bryant opens up on his path to the pros and what keeps him busy when he’s off the course

By Jon Rizzi

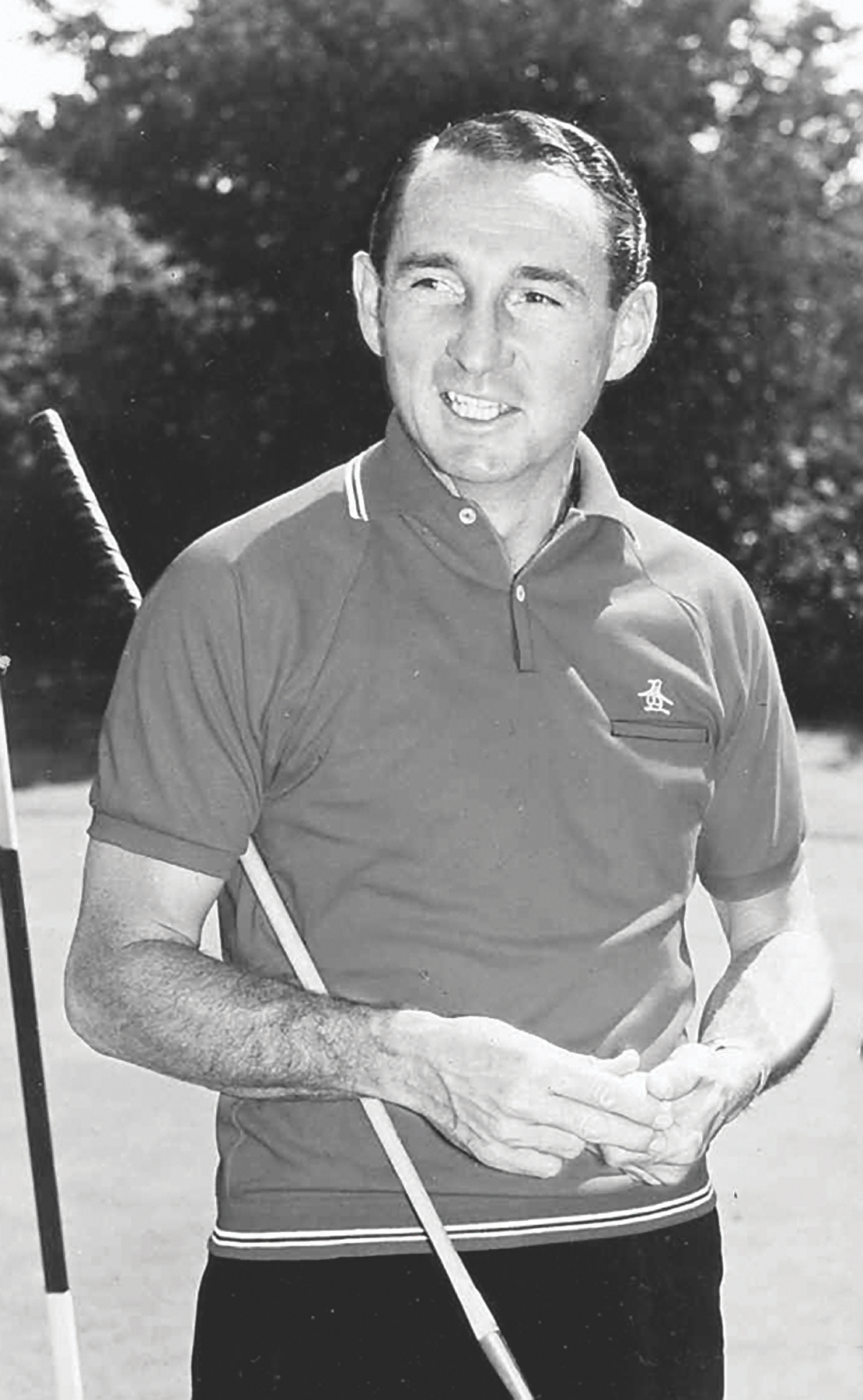

On November 11, attendees from around the state and country filled The Broadmoor’s Cheyenne Mountain Lodge for the Celebration of Life for Dow Finsterwald. A week earlier, The Broadmoor’s PGA director of golf from 1963 to 1991 had passed away at the age of 93.

“The words I use to describe Dow are dapper, classy, eloquent, caring and compassionate,” his eventual successor, PGA Director of Golf Russ Miller, shared.

“He and I could wear the exact same outfit, and he’d be an A-plus and I’d be a C-plus at best,” Miller joked. “One time, he was wearing a pink shirt with a yellow sweater tied around his shoulders, like Arnold Palmer used to, and my wife, Linda, told me, ‘He can pull that off; don’t you even think about it.’”

Like Finsterwald, Miller was married to a woman named Linda who predeceased him, and the consolation each man offered the other in the painful aftermath revealed a relationship deeper than golf. “I should add empathetic to that list of words,” Miller says.

Finsterwald was a professional golfer in addition to becoming a golf professional. Five years before arriving at The Broadmoor, the Athens, Ohio, native triumphed in the 1958 PGA Championship—the lone major among his 12 PGA TOUR victories (or 11, depending on whether you count the 1955 British Columbia Open) and was named the 1958 PGA TOUR Player of the Year.

In 1957, the year he won the Vardon Trophy for lowest scoring average on the PGA TOUR, he lost the finals of the last PGA Championship contested as match play, 3 and 1, to TOUR rookie Lionel Hebert. Two other excruciating losses came against Arnold Palmer in the ’60 and ’62 Masters—the latter in an 18-hole Monday playoff, the former after the two strokes he was penalized in the first round for violating a local rule proved the ultimate margin of defeat.

He’d brought the “infraction” to the attention of the committee. He later became a Rules official at the Masters, beginning in 1977 and served on the USGA Rules of Golf committee from 1979-’81. At the Colorado Open he was “the glue of the rules,” according to Colorado Golf Famer Gary Potter.

Finsterwald compiled a 9-3-1 record as a player in four Ryder Cups, and he captained the 1977 U.S. squad to a resounding victory over the last team drawn solely from Great Britain and Ireland. That trophy shines from inside a glass case in The Broadmoor’s Heritage Hallway between the golf shop and The Grille.

Finsterwald’s involvement in golf did not end when he left The Broadmoor. Having helped Cherry Hills land the 1978 US Open and 1985 PGA Championship, he worked at bringing the 1993 U.S. Senior Open there and the 1995 US Women’s Open to The Broadmoor.

Starting in 1981, Dow and Linda Finsterwald would winter at a house in Bay Hill, the club owned by his best friend, Arnold Palmer, in Orlando, Florida. Born four days apart, Finsterwald and Palmer became friends in 1948 during a college tournament at Raleigh Country Club in North Carolina. Finsterwald played for Ohio University and Palmer for Wake Forest.

“My father had a term for people who weren’t good: Revolving SOBs,” Finsterwald once said. “It didn’t matter what angle you looked at them, they were still SOBs. Well, Arnold was a revolving good guy. He didn’t just excel on the golf course, he excelled in life.”

They both won their first PGA TOUR events in 1955. The following year, Palmer would win the first of his four Masters. Finsterwald’s only major, that PGA, was the one Palmer didn’t win, and in Palmer’s epic victory the 1960 U.S. Open at Cherry Hills, “Finster” finished tied for third, three shots behind.

In September of 1963, Finsterwald competed in the Denver Open Invitational at Denver Country Club, but he hadn’t gone to Colorado Springs.

However, having played in multiple Masters tournaments, Finsterwald had made a big impression on Augusta National Golf Club’s Head PGA Professional “Big Ed” Dudley, the 6-foot-4 Georgian who during the summer held the same job at The Broadmoor.

Dudley reportedly told Broadmoor President Thayer Tutt that if anything should happen to him, Tutt should contact Finsterwald for the job. In October, Tutt, who’d briefly met Finsterwald in Atlanta during the 1963 Ryder Cup, called him days after the U.S. victory because Dudley, age 62, had died of a heart attack.

Then 34 and still competitive on the PGA TOUR, Finsterwald had seen how Sam Snead had successfully balanced his playing schedule with his professional duties at West Virginia’s fabled Greenbrier.

“I knew it could be done, but there had to be some flexibility,” Finsterwald said. “I was to employ a full-time golf professional, but the ones I hired didn’t work out.”

Finsterwald continued to compete, but never won another PGA TOUR or PGA Senior Tour event. His children—Dow Jr., Ref, John and Jane—all grew up at The Broadmoor and worked in various capacities at the resort.

During the first year of his tenure, The Broadmoor’s Robert Trent Jones-designed West Course opened, doubling the size of the golf operation.

Three years later, the West hosted the U.S. Amateur. “Golf was not a long season but an intense season,” Finsterwald said.

In 1966 University of Colorado football coach Eddie Crowder called The Broadmoor pro about a star defensive back who’d asked to be excused from spring practice to play on the golf team. “So, he told him, ‘If Dow Finsterwald says you’re that good, I’ll release you.’”

After the two played holes 16, 17 and 3 on the East, Finsterwald told the coach, “I don’t know what’s in his chest or between his ears, but he’s got the skills to become a professional.” The following spring, that All-Big 8 defensive back, Hale Irwin, would win the NCAA Men’s Golf Championship and the Broadmoor Invitation before launching his World Golf Hall of Fame career.

Another of Finsterwald’s memories of The Broadmoor involved Palmer, who after a heartbreaking 18-hole Monday playoff loss to Billy Casper in the 1966 U.S. Open at San Francisco’s Olympic Club, visited his pal at The Broadmoor.

“He was signing autographs for dishwashers, waiters and guests in the Penrose Room,” Finsterwald remembered. “He never once refused a request. All he did was smile. You might have thought he’d won the Open.”

That visit, according to Finsterwald, resulted in Palmer designing The Broadmoor’s South Course—and Finsterwald helped the process along. Designed by Palmer and Ed Seay, the spectacular layout on the side of Cheyenne Mountain opened in 1976 and hosted the 1982 U.S. Women’s Amateur, won for the third consecutive year by Juli Inkster.

Finsterwald hired Hal Douglass—the father of Broadmoor member and PGA TOUR player Dale Douglass—to be the PGA head professional on the South Course. He’d hold the job for 18 years. Finsterwald also had strong relationships with The Broadmoor’s female amateur stars: Judy Bell, Barbara McIntire, Tish Preuss and Nancy Roth Syms.

“Dow was truly a great club professional,” remembers Colorado Golf Hall of Famer Maggie Giesenhagen, who was a Broadmoor Golf Club member in the 1970s and 1980s. “He acquired tickets to The Masters for my husband Bill and me several times back in the 1980s. He was so supportive of the Broadmoor Ladies Invitation; he was always out on the course watching play and helping with rulings. He loved to have fun!”

Ever self-deprecating, he often told the story of visiting Jerry Pittman, the PGA professional at Seminole in the winter of 1991.

“He asked, ‘Dow, are you still at The Broadmoor?’

“I said, ‘No they retired me a few months ago.’

“‘How long were you there?’ he asked.

“‘Just under 30 years.’

“He said, ‘Goddamn, you had them fooled for a long time.’”

Until about 2020, he would come to The Broadmoor to practice or play. I once spotted him near the plaque honoring him near the practice green and asked about his legendary short game. He responded with a laugh: “Every part of my game is short now.”

He strongly promoted Colorado’s First Tee chapters, regularly attended fundraising events, and as recently as two months ago, he was having lunch every day at the Golf Grille, making his way with a walker down the Heritage Hallway—past cases displaying trophies, his Ryder Cup bag and other mementoes of his brilliant career.

Between 1955 and 1958, Finsterwald made an astounding 72 consecutive cuts during a period when the “cut meant being among the top 25 or so players who finished “in the money,” not just getting to play the weekend. At the time, that streak ranked second only to Byron Nelson’s; it currently ranks fifth behind those of Tiger Woods, Nelson, Jack Nicklaus and Hale Irwin.

You’ll find all four of those golfers—as well as no. 6, Tom Kite—in the World Golf Hall of Fame, but not Finsterwald. He’s been inducted into the PGA of America Hall of Fame, Colorado Golf Hall of Fame, Colorado Sports Hall of Fame, Ohio University Athletics Hall of Fame and the Ohio Golf Association Hall of Fame. However, the World Golf Hall of Fame—which in 2023 will move from St. Augustine to Pinehurst Resort—has overlooked him.

This came as a surprise to some board members of Colorado Golf Hall of Fame, which itself is relocating to The Broadmoor next year. During early discussions about creating a special display for inductees also enshrined in the World Golf Hall of Fame, Finsterwald’s name came up as routinely as those of Hale Irwin, Judy Bell, Paul Runyan and Babe Zaharias.

When corrected, one of the directors rhetorically asked, “How can Dow not be in the World Golf Hall of Fame?”

At least two eulogists at Cheyenne Mountain Lodge evidently wondered the same thing. After describing how Finsterwald—whom they had brought in for customer golf outings—made a call to U.S. Steel Chairman David Roderick that saved their steel business in the 1970s, Greer Industries’ John Raese and Bob Gwynne praised the humility of a man whose best friend was Arnold Palmer and who’d played golf with presidents, movie stars and industrialists— but never boasted about it.

Raese and Gwynne retained Finsterwald as a consultant as they designed and built Pikewood National Golf Club in Morgantown. The club opened in 2009, won Golf Digest’s best new private club and ranks 33 on the publication’s 100 Greatest Courses list. Finsterwald became pro emeritus.

They closed their remarks by saying, “We’re trying to get him in the World Golf Hall of Fame.”

“I would have bet my pants he was already in,” Miller remembers thinking.

Whether or not Dow Finsterwald gets into a sixth Hall of Fame ultimately matters not.

“He did all he could for the game,” said his son, Dow Finsterwald, Jr., who recently retired as the head PGA professional at Colonial Country Club in Fort Worth. “He enjoyed his friends and they always remembered. He loved the rules, and he cared about the game. He had a wonderful life and he felt like for sure it was complete.”

This article can also be found in the Winter 2022 Issue of Colorado AvidGolfer.

Colorado AvidGolfer is the state’s leading resource for golf and the lifestyle that surrounds it, publishing eight issues annually and proudly delivering daily content via coloradoavidgolfer.com.

Colorado State grad Davis Bryant opens up on his path to the pros and what keeps him busy when he’s off the course

The staff at Dream Makers Landscape is ready to help you enhance the look and feel of your property with our exceptional landscaping projects