Drive Away Hunger Golf Classic 2025

Join Community Table on August 25 at Fossil Trace Golf Club

By Andy Bigford

GOLF IS FULL of legendary rags-to-riches tales, from Sam Snead learning the game with a club carved from a tree limb to Lee Trevino growing up in a shack without plumbing or electricity. Then there’s Gene “The Rock” Torres, one of Colorado’s most decorated professionals ever with 80-plus wins, who got his start in the game by shoveling coal.

Growing up in hardscrabble Trinidad in the 1940s, the son of an electrician, Torres found a job feeding the furnace in the winter at the Trinidad muni, which he parlayed into hauling double bags out on the course when summer arrived. One of the regulars gave him a secondhand club and he taught himself the game, forging a career that would include four decades of teaching, coaching, mentoring and winning golf tournaments in Colorado and all over the Southwest.

Torres would settle 120 miles south of the state line in Las Vegas, N.M., where he spent 43 years as the pro at the New Mexico Highlands University’s nine-hole course, which is now named after him; as a professor of Physical Education; as the NMHU golf coach; and as a mentor to thousands of golfers, from professionals to newcomers.

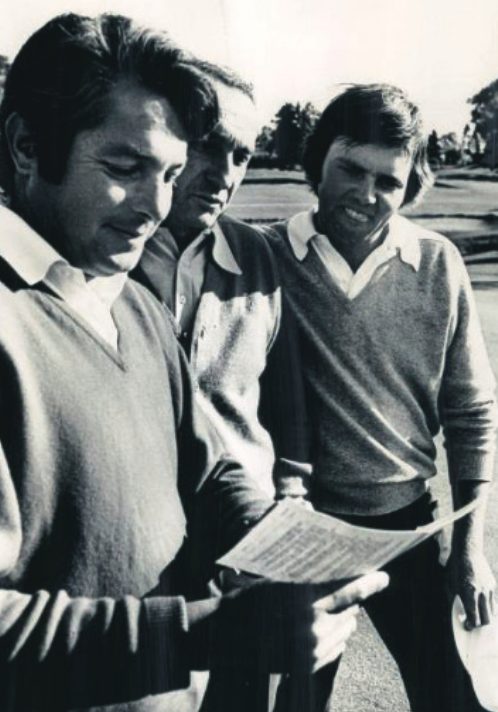

In his spare time, he compiled an eyepopping playing record, winning the New Mexico Open four years in a row (until Trevino, fresh off wins in the British and U.S. opens, ended his streak—by one shot); winning the Colorado Open in 1972 (after having blown a seven-shot lead to Dave Hill, a three-time Ryder Cup member, the previous year); the Wyoming Open in 1974; and generally going low around the country, including a record-setting 62 at Pinehurst, N.C., in the 250 team 1971 National Pro-Am. He won the Conrad Hilton Open and San Juan Open four times each, was the six-time Sun Country PGA Section champion (incorporating New Mexico and El Paso, Texas), and is believed to be the first New Mexican to win a U.S. Open regional qualifier in 1973 when he earned a spot in the Open held at Oakmont.

Despite all the accomplishments on the course and practice tee, Torres, who passed away in 2005, has not been inducted into the NewMexico Sports Hall of Fame (the state has no stand-alone golf hall) or the Colorado Golf Hall of Fame, though he has been nominated for both.

“I thought he was deserving. I don’t understand it,” says Colorado native Larry Webb, who won the 1980 Colorado Open and was inducted into the Colorado Hall in 2000. “One of my favorite people in the world. He was a major part of Colorado golf back when I started playing.” Webb, now the head pro at Gillette Golf Club in Wyoming, recalls Torres as a true gentleman who was always eager to help. “I loved competing with him, and I loved having him teach me.”

Starting with that single hand-me-down club, Torres idolized Ben Hogan, often playing alone with two balls: His own and Hogan’s. “I never beat Hogan,” he would say. Torres won the Colorado High School Association state championship in 1956 (before size classifications) and would also expand his horizons, traveling to Columbus, Ga., to finish tied for 10th in the National Jaycees Youth Tournament with a kid named Jack Nicklaus. He attended Adams State College in Alamosa for a semester but struggled to make ends meet and ultimately joined the Navy. The admiral at boot camp saw Torres’ golf record and made him a sort of base ambassador, allowing him to tour and put on exhibitions. When he was assigned permanent duty, there was a new admiral in charge, and he spent almost four years at sea aboard the USS Shangri-La.

Out of the Navy, Torres had the good fortune to connect with Thomas C. Donnelly, the new president at NMHU and an avid golfer. Donnelly wanted to start a golf team at NMHU, and he also wanted to offer instruction to a wider swath of students. Torres stepped into the role in 1962, and though the golf team was disbanded in 1987, he worked tirelessly at the course, and at teaching, almost until his death.

It was never easy, especially after Donnelly left; at times Torres did everything, including cutting the greens, typically working seven days a week. (His wife Dodie often ran the pro shop, and three of their four kids also pitched in.) In 1972, Torres qualified for the PGA Championship at Oakland Hills outside Detroit. He played a practice round with his friend Trevino, who gave him a couple putters and encouraged him to keep grinding. Torres made the cut and qualified for the next PGA stop in Westchester, N.Y., but opted to head home, where he would be hosting the Rough Riders event at his home course. “This tournament comes first,” Torres told the media.

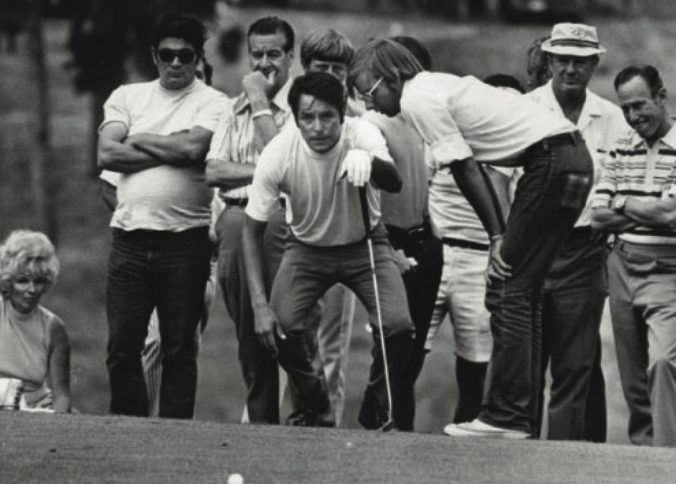

The Rough Riders was a prestigious amateur tournament that Torres founded on the NMHU course. Even though it was only a nine-holer with push-up greens, the course was cut out of swamp bottoms and required long, accurate carries along with a deft short game. Torres would double cut and roll the greens, so the course played hard and fast. “You wanted to win the tournament because Gene was in charge,” says Tom Verlande, who competed there as an amateur and then against Torres as a professional and is now the head pro at Black Mesa Country Club in Española, New Mexico. “He was—by far—the best player in the state.”

Torres was not a straight driver of the ball, but he was an uncanny escape artist; his son Gene “Geno” Torres says that while his dad idolized Hogan, his style resembled Seve Ballesteros. Verlande recalls seeing him in the final round of the Conrad Hilton Open in Sacorro, N.M., where Torres hit just four greens in regulation but shot a 71 to hang on for the win.

“It was the most amazing chipping exhibition that I’ve ever seen.”

Torres was a Class A PGA member despite never having taken a formal lesson, and an untenured professor despite only having completed one semester of college. The NMHU golf team never had much of a budget and Torres would often fund travel out of his pocket, but they compiled a winning record and once beat the University of Colorado when its team was ranked 12th nationally.

“Gene was a great player and an even better person,” says Denver native Joe Pinson, who was recruited to NMHU by Torres. “I basically went there blind without seeing the town or the golf course. I remember taking the exit off I-25 into Las Vegas and thinking, ‘What in the hell did I get myself into?’ It was the best four years and I wouldn’t trade it for anything. He was such a good player, teacher, shotmaker, mentor, and the imagination he had for picturing and hitting golf shots was amazing.” Pinson is the long-tenured head pro at Overland Park Golf Course (he had grown up across the street), and now says, “A lot of my teaching methods came from my years with Gene.”

Golfers traveled from Arizona and Colorado seeking his instruction. Through thick and thin (mostly the latter), Torres kept the course running, often arriving by 7 a.m. and closing at 9 p.m. “All the kids loved him,” Verlande says. “The only thing keeping that course open was him.”

“He shed his blood and tears to keep it going,” says his wife, Dodie. They met in high school in Trinidad, where she hailed from a ranching family; Dodie eventually learned the game herself and became a multiple city champion.

Their son Geno caddied for his dad in his younger years, would become the head pro at Santa Fe Country Club, and dabbled with the mini-tours, once qualifying for a Nike event. He could never match his dad, who he recalls once told him that after spending almost four years on that Navy ship, he never recovered his putting stroke or touch. Geno also unraveled the origins of that “La Piedra” nickname: Everyone knew of and wanted to talk to his dad, but Gene didn’t know most of them…so he called everyone “Rock.” When asked why, he’d enthusiastically reply, “’Cause you got a rock-solid game.” Verlande remembers it well: “Everybody was Rock, and everybody would call him Rock.”

Torres did line up sponsors for PGA TOUR runs on a couple of occasions, but in those days that meant mostly Monday qualifiers, and he never stuck with it past a few months. He always stayed in good shape, but never mounted a Champions Tour effort either, though he did win numerous senior and super senior state tournaments. Geno says his dad never had much time to practice, and that he considered “hitting a large bucket of balls” as tournament prep. When asked why he didn’t practice more, Torres would say, “It’s all in my head.” But fellow pro Webb says Torres certainly knew how to keep his game sharp, including chipping around those turtle-back greens on the NMHU course when he had a free moment. (The course was completely redesigned in 2008.)

Verlande will never forget Trevino and Torres dueling in the final round in that 1972 New Mexico Open, when Trevino made a birdie down the stretch to pull ahead. Both were charismatic gallery favorites, but Torres was always diplomatic —fierce but friendly. “The Rock’s way of talking [smack] was just beating you,” Verlande says. There were exceptions. Webb recalls going down to Las Vegas to say goodbye to his old friend in the final days, when Torres’s battle with stomach cancer had withered him to 120 lbs. “He leaned over to me and said, ‘Webby, I’ll take you out and beat you right now,’” Webb recalls. “He was a great man.”

Dodie Torres finally gave up several years ago on the effort to get her husband into the New Mexico Sports Hall of Fame. Gene did earn the Lifetime Achievement Award from the PGA, its highest honor, and was inducted into the NMHU Hall of Honor. Fellow pro Verlande, bothered by the lack of recognition, founded a Northern New Mexico Golf Hall of Fame and made The Rock its first inductee. Bernie Mares, a Trinidad native who had followed Torres career closely from a young age, led the unsuccessful effort to get him enshrined in the Colorado Golf Hall of Fame back in 2008.

“He didn’t live in Colorado,” was the Hall’s logic, he recalls. “That’s bull.” Like many others, Mares remains captivated by Torres’ golf, which he describes as “Tiger-esque,” and even more so with his impact on people. “My life would be complete if I could see Gene inducted into the Hall.”

Andy Bigford, a Colorado AvidGolfer contributor, is working on the third installment in the Ski Inc. book series with Chris Diamond.

This article was also featured in the July 2020 issue of Colorado AvidGolfer.

Colorado AvidGolfer is the state’s leading resource for golf and the lifestyle that surrounds it, publishing eight issues annually and proudly delivering daily content via coloradoavidgolfer.com.

Join Community Table on August 25 at Fossil Trace Golf Club

Steamboat Springs is like a secret only you and your friends know

Vail Valley is home to an endless array of summer outdoor pursuits