Being Frank

Colorado’s most famous golfing chef, FRANK BONANNO, is fluent in both cooking knives and 9-irons.

By: John Lehndorff

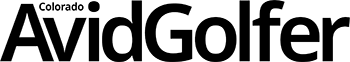

Photographs By: Ehren Joseph

“It’s focus. It’s intensity—90% of golf and cooking is between your two ears.”

IF FATE HAD simply twisted a little bit differently, Frank Bonanno might be teaching you how to putt instead of serving you his duo of duck with Korean white bean ragout or his famous butter-poached lobster mac-n-cheese. After all, this is a guy who shot a 75 at Pebble Beach and passed his PGA player ability test. Not long ago, he shot a 68 on his home course.

Colorado’s most famous golfing chef, FRANK BONANNO, is fluent in both cooking knives and 9-irons.

For most of his colorful life, Frank Bonanno has pursued dual passions—food and golf—which have intersected in some unexpected ways.

You may not know his face, but if you love to eat you’ve probably tasted his food at some point in the last 20 years in Denver. Arguably the state’s best-known chef, Frank Bonanno is co-owner of Bonanno Concepts, an empire of nine eateries ranging from fine dining at Mizuna and Luca to casual fare at Salt & Grinder and the multi-stall Denver Milk Market. Despite the pandemic, none of his restaurants have been permanently shuttered.

According to Mark Antonation, long-time Food & Drink Editor of Westword, Bonanno has left an indelible mark on dining in Denver.

“Frank was the first big-name Denver chef of the new century,” Antonation says. “I don’t know of any other chef in Colorado who has covered the scope of cuisines that Frank has. He ushered in this new era of fine casual fine dining in Denver.”

In addition to penning two cookbooks, Bonanno, 53, has also received multiple nominations for the James Beard Foundation Awards and hosted “Chef Driven,” a Colorado Public Television series.

‘I ALWAYS THOUGHT GOLF WAS PRETTY STUPID’

Bonanno grew up in a food-focused Sicilian- American family in Demarest, New Jersey watching Julia Child and Jack Nicklaus on TV and expecting to be a tennis player.

“When I was a kid, I always thought golf was pretty stupid. I played tennis competitively. My mother told me I should play golf. She said: ‘You can play tennis really good right now, but you can play golf the rest of your life.’ I did not believe her at the time,” Bonanno says.

Golf didn’t sound smart until he moved to Denver to attend the University of Denver’s Daniels College of Business, and, he admits, to ski as much as possible. “I was working at Anthony’s Pizza and decided to teach myself how to play golf. I lived at Overland Golf Course but I didn’t play many rounds. I’d chip and then gather all the balls. Then I would putt. Then I would finally hit them out onto the range. Being the cheap person I was, I’d make a $10 bucket of balls last for hours. I did that for a year and a half. It was fun,” he says.

A CAREER TURNING POINT

It didn’t take long before the lure of culinary overcame the solidity of the fiduciary and he headed to the prestigious Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, NY, to become a chef.Bonanno returned to Denver after graduation and met his soon-to-be wife, Jacqueline.

“I was student teaching and waiting tables at the Rattlesnake Club in Denver and Frank was doing an externship. I always knew Frank was into golf, but I didn’t realize then what a big deal it was going to be,” says Jacqueline Bonanno.

The chef began a stint at the legendary Mel’s Bar and Grill in Cherry Creek and he also started working on his game. “I spent all my days off at Overland because they had the best practice facilities,” he says.

Surprisingly, getting fired from Mel’s in 2000 improved Bonanno’s game and almost changed his career. “I got three months’ severance and was playing pretty good golf in the low 80s but I was still getting hustled and losing money to some of the guys I played with. I went and practiced seven days a week and then I’d go out and play 36 holes. I was considering becoming a teaching professional at a club and took my PGA player ability test. I think you had to shoot 146 over two days—and I just barely passed playing at Park Hill,” he says.

That’s when Bonanno heard about the available restaurant space that would become his first restaurant, Mizuna.

“I still loved cooking more than I loved golf,” he says.

THE ZEN OF GOLF AND COOKING

To Frank Bonanno, there is a crystal- clear correlation between playing golf and cooking. “It’s focus. It’s intensity—90% of golf and cooking is between your two ears. When you’re working one station in the kitchen you are reliant on your preparation. Can I make the same lobster fra diavolo, the same fussili, and the same spaghetti pomodoro perfectly for four hours during a dinner rush,” Bonanno says.

“When it comes to golf, can I hit a driver, an iron, a wedge and can I putt and can I do them consistently?”

IMPRESSIONS OF AN ARTIST WHO GOLFS

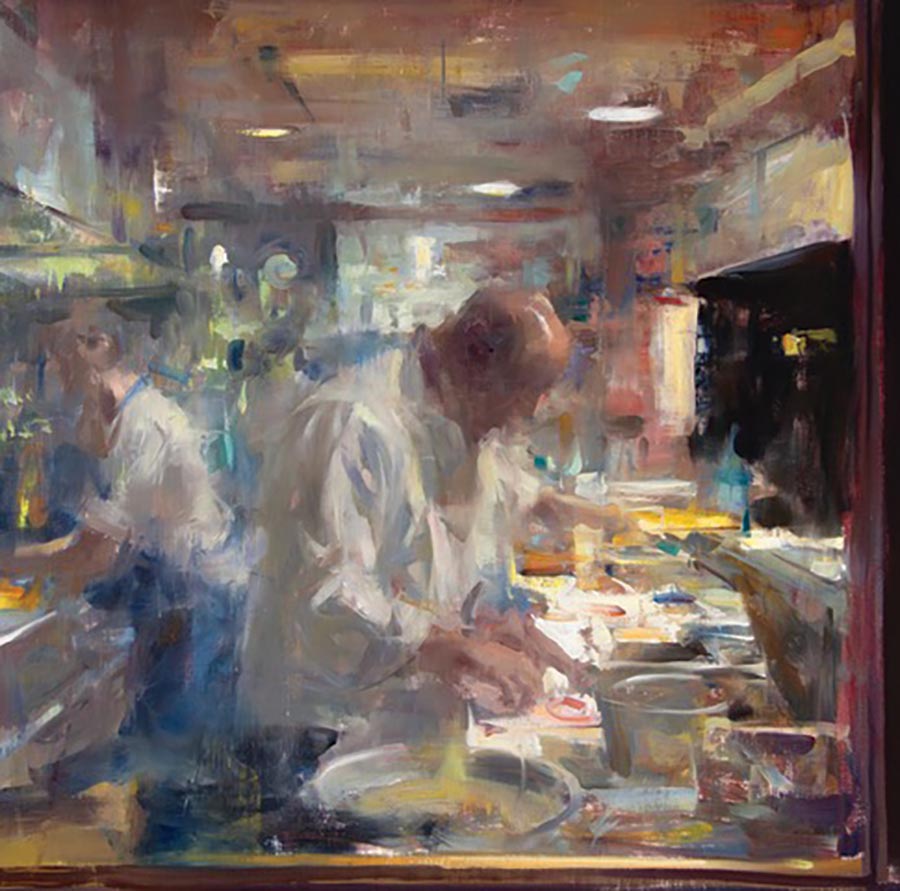

Quang Ho is a renowned Denver fine artist with a strong interest in both good food and playing golf.

“I was dining at Mizuna when it first opened. I asked if I could paint Frank working in the kitchen. They loved it and for a while we traded food for art,” Ho says. His impressionistic interpretations of kitchen and restaurant life have since become an iconic part of the ambiance at every Bonanno eatery.

“In the beginning, I used to beat him all the time. Now, I never beat him. He hits it a mile for a guy that’s not that tall,” Ho says.

Quang Ho remembers one shot that defines Bonanno’s game to him. “I was beating him this one day. He was about 175 yards out. He hits this shot and it flew and one-bounced into the hole. It took out a chunk of grass on the edge of the hole and stuck in there. Never seen anything like it. A hole in two,” Ho says.

If you ask the guys who play with him if Bonanno is competitive, they laugh.

“Frank’s game is fast. He does that Frank walk to the ball and then he’s like: Boom. Boom. Boom. He’s always in a hurry, just like in the restaurant,” Ho says.

WORKING FOR—AND PLAYING AGAINST—BONANNO

Frank Bonanno’s biggest impact on local dining may end up being his role as a mentor. “He’s always been really good at generating talented chefs that are doing new things in Denver,” says Antonation. Bonanno’s culinary offspring can be found running and working at Olivia, River Bear American Meats, Fruition and Mercantile, among other establishments.

Tim Hershberger worked for Frank Bonanno at Mizuna restaurant for four years and now is a sommelier at Mercantile Dining & Provision in Denver.

“Frank on the golf course is pretty much the same as Frank in the restaurant; pretty relaxed and even-keeled,” Tim Hershberger says.

“He’s strong and hits it pretty accurately. The last time we played he did great, but the course at Lakewood ate my lunch. He knows the course, but it’s another thing to execute,” Hershberger says.

Lakewood Country Club, which Bonanno joined in 2011, was the site of the best round in his life so far. “My lowest score ever was a 68. I think I started the round eagle, birdie and eagle,” he says.

It’s all the more impressive because, in a three-year period starting in 2015, Bonanno had three hip replacement surgeries because one of the replacements didn’t function properly.

THE FAMILY THAT DOESN’T GOLF TOGETHER

Now, he’s in good shape, reports Jacqueline Bonanno—not that she bears witness to any of his golfing prowess.

“I am a golf widow by choice,” she says. “I do not golf. Between working together and home, we need that. Frank really needs something that he does without me.”

Frank Bonanno does play on occasion with their sons—Marco, 17, and Luca, 18. Both have taken some golf lessons but, according to Bonanno, it’s like father, like sons.

“We go out and goof around, but they aren’t into it yet. Maybe when they grow up,” he says with a chuckle.

Jacqueline Bonanno notes an aspect of her husband’s personality that may surprise many of his customers and friends. “Frank is a shoe whore, a super shoe addict. He doesn’t look like the type but he has a ton of special chef shoes. He used to have more than 30 pairs of golf shoes that he kept in back of his Jeep but then someone stole all of them. He hasn’t quite built up his collection again,” she says.

has forced a change in the way Bonanno’s restaurants do business. “Before March, if you asked for to-go or delivery at Luca, we would have laughed at you,” he says.

A YEAR OF CLOSING, OPENING AND COPING

Over the decades, Frank Bonanno has had to deal with many business challenges including several serious recessions. Those were a breeze compared to the past 12 months or so, he says.

“On March 5th, I had 485 employees. By March 17, I only had 18 employees. It was terrible. Slowly I’ve been able to hire some of them back. We changed the way we operated and what we had on the menu. Listen, before March, if you asked for to-go or delivery at Luca, we would have laughed at you. Now we’re good at it,” Bonanno says.

All of his operations closed temporarily but none permanently, but Bonanno expects the restaurant world to change. “Restaurants were already struggling to make a profit before the pandemic. The days of having so many employees—a bartender, barback, bus boy, prep cook, A.M. sous chef, polisher— well, those days are gone,” he says.

Tipping may also be a thing of the past. “We have already gone to being a non- tipping restaurant at Mizuna. We do a set fee on each table. We divide that up and everyone working in the restaurant has an hourly wage,” Bonanno says.

Because of the pandemic, Bonanno has spent a lot more time in his kitchens simply cooking. If the truth be known, he doesn’t mind so much.

“Life may suck, but I can go roll pasta for three hours and forget everything. There are parts of the job I don’t love, like dealing with finances and landlords, but when service starts, I love what I do,”he says.

“By this summer, I hope things have improved so I can play a lot of golf.”

This article was also featured in the Spring Issue of Colorado AvidGolfer.

Colorado AvidGolfer is the state’s leading resource for golf and the lifestyle that surrounds it, publishing eight issues annually and proudly delivering daily content via coloradoavidgolfer.com.

Fixing the Chicken Wing with Pro Golfer Marisa Messana

Golftec’s Nick Clearwater Takes Marisa Through a Lesson